Can AAC support those with cerebral palsy to communicate? This blog answers this very important question.

AAC for Cerebral Palsy

Communication is one of the most valuable assets we have as humans. So much so that we think ability to interact gets compromised in the absence or paucity of traditional speech. AAC comes to be a perfect solution here.

With training, AAC users can communicate at a level that was not expected of them. This holds true for those with conditions like cerebral palsy as well. AAC empowers them to express ideas, opinions, and thoughts. It also enhances their ability to converse with others.

Communication Profile of Children With Cerebral Palsy

Cerebral palsy is a complex disorder where children are at increased risk for a variety of speech and language problems. Motor impairment, along with communication difficulties, puts children at risk of being unable to meet all their communication needs using speech.

Children with cerebral palsy present with a variety of speech and language profiles. This varies from no speech-motor involvement and typical language / cognition to being unable to speak (Hustad, Gorton, & Lee, 2010).

A recent study of 2-year-old children with cerebral palsy by Hustad et al (2014) found that 85% of them had significant speech and language impairments.

Parental Priorities and Focus of Therapy

Chiarello et al. (2010) conducted a study to find out family priorities in intervention for their children with cerebral palsy. The authors found that families rank communication at number three, behind self-care and mobility. Pennington and Noble (2010) also reported the same. In their study, they interviewed parents of preschool children with motor disorders in England.

While receiving speech and language services, the primary focus of therapy is on feeding and oral-motor skills. Facilitating functional communication did not feature prominently. They also found that children with Cerebral Palsy receive scarce AAC intervention.

Hustad and Miles examined speech and language services for 4-year-old children with cerebral palsy in 2010. They found that just over half of the children who needed AAC actually had AAC-focused objectives in their therapy plan.

The Need for AAC

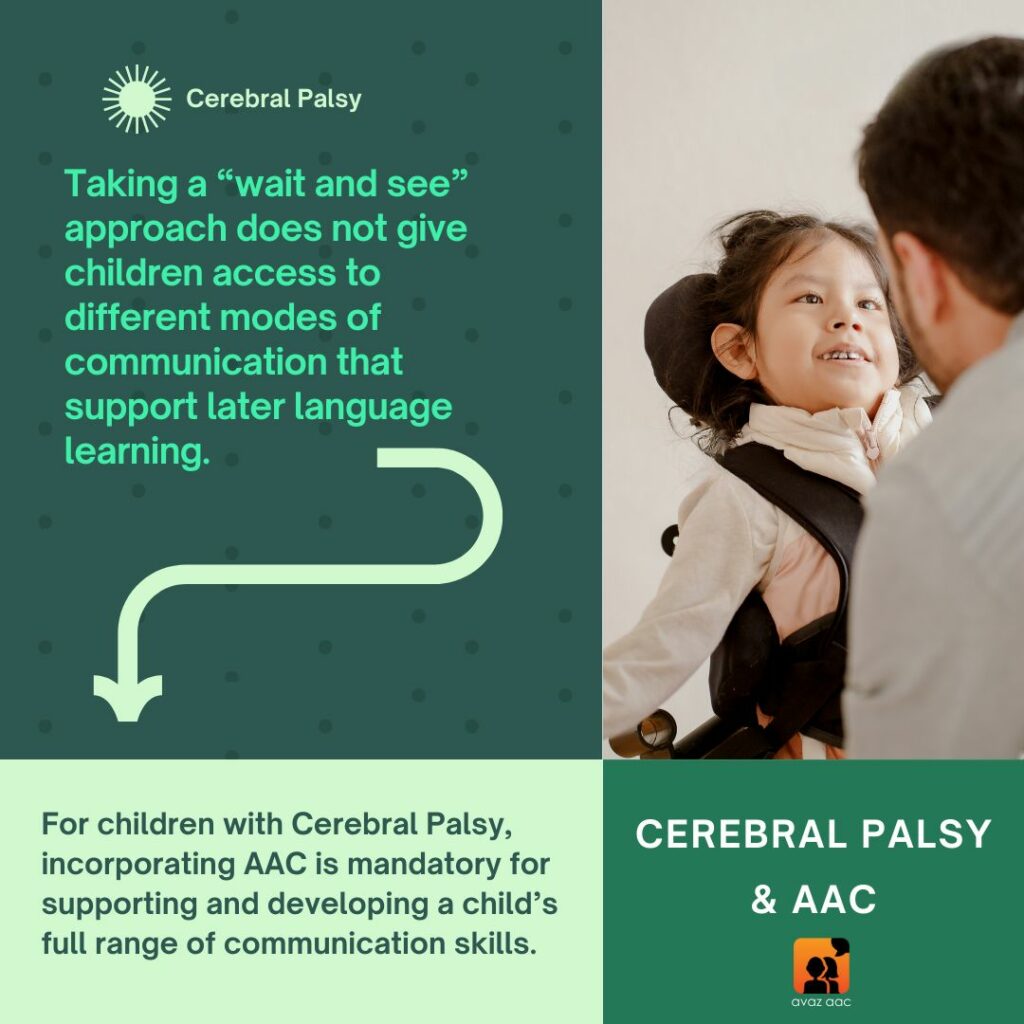

AAC is an essential part of early intervention to facilitate speech and language development (Cress & Marvin, 2003; Light & McNaughton, 2012b. For children with cerebral palsy, AAC is essential for supporting and developing a child’s full range of communication skills (Pennington, 2008; Clarke & Price, 2012). According to Cress & Marvin, a “wait and see” approach limits a child’s access to different modes of communication for language learning.

Introducing AAC to children with cerebral palsy at an early age optimizes communication and language skills (Geytenbeek, 2011). Some parents of older children with cerebral palsy reported that they should have introduced AAC to their children much earlier (Marshall & Goldbart, 2008). Research has repeatedly shown that introducing AAC at an early age does not stop or interfere with the development of speech (Romski et al., 2010; Millar, Light, & Schlosser, 2006; Schlosser & Wendt, 2008).

This is not to say that AAC learning is without its challenges. The benefits far outweigh any hurdles faced picking up communication with AAC.

Moving in the Right Direction

Service providers must focus on supporting receptive language through AAC strategies. It supports communicators to learn meanings between symbols and their referents. Learners eventually produce AAC symbols. Some children go on to develop spoken language skills (Sevcik, 2006).

The same stands true for children with vision impairments. Having vision issues makes AAC intervention more difficult, especially for a child with multiple disabilities. However, introducing tangible symbols for children with both visual and motor impairments is very beneficial. It can improve comprehension. It can also support effective communication, and development of sophisticated symbol systems (Roche et al., 2014).

Aided language stimulation (Goossens’, 1989) and augmented input (Romski & Sevcik, 2003) where picture symbol is paired with speech – foster comprehension and production (Brady, 2000; Millar et al., 2006; Dada & Alant, 2009). We can be implement it successfully with parental involvement (Jonsson, Kristoffersson, Ferm, & Thunberg, 2011; Romski et al., 2010).

Exploring Options

Direct access to AAC devices maybe difficult for some children with Cerebral Palsy. Today, there are multiple options that improve access to the AAC system.

Eye tracking is one such development. This can be very useful for children who find it difficult to point directly at letters or symbols.

When the physical disability limits the child’s mobility, communication boards, and high-tech devices can be mounted to wheelchairs. We can adjust the angle of the mount to suit every child’s motor and visual needs.

Benefits of AAC for Children with Cerebral Palsy

Life Saving:

A child has specific ailments or pains, they must have a way to communicate what hurts and where. AAC can support them to get appropriate medical help at the earliest – rather than parents trying to guess the problem.

Educational:

Another benefit of AAC is increasing their knowledge through learning. It allows them to ask questions in class and clarify their doubts. Their vocabulary increases and they understand concepts better. Through AAC supported literacy development they move towards employment and independence in adulthood.

Conclusion

In the absence of speech, AAC can empower a child to control their environment. It enables them to express their needs and thoughts to others. They can develop bonds with others and have a better quality of life. We also have AAC users contributing to the society.

AAC is not a substitute for speech but it is a complement. Just like how speech allows a person to communicate, communication devices enhance a person’s ability to be heard.

WRITTEN BY

Niveditha Ryali

Speech – Language – Swallowing Therapist

I have years of experience that comes from working in NHS(UK), special schools, hospitals and private practice. My passions are working on improving Speech, Language and Swallowing skills in children and adults. I also strive to facilitate early communication in children with complex communication needs, thereby improving parent-child bonding.